| ||

|

Born: 17-Dec-1807

Born: 17-Dec-1807

Birthplace: Haverhill, MA

Died: 7-Sep-1892

Location of death: Hampton Falls, NH

Cause of death: unspecified

Remains: Buried, Amesbury, MA

Gender: Male

Religion: Quaker

Race or Ethnicity: White

Occupation: Poet, Activist

Nationality: United States

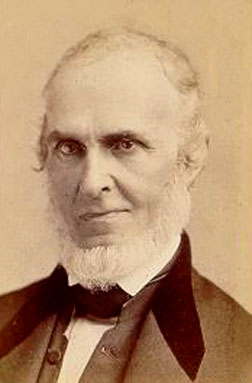

Executive summary: American abolitionist poet

John Greenleaf Whittier, America's "Quaker poet" of freedom, faith and the sentiment of the common people, was born in a Merrimack Valley farmhouse, Haverhill, Massachusetts, on the 17th of December 1807. The dwelling was built in the 17th century by his ancestor, the sturdy immigrant, Thomas Whittier, notable through his efforts to secure toleration for the disciples of George Fox in New England. Thomas's son Joseph joined the Society of Friends and bore his share of obloquy. Successive generations obeyed the monitions of the Inner Light. The poet was born in the faith, and adhered to its liberalized tenets, its garb and speech, throughout his lifetime. His father, John, was a farmer of limited means but independent spirit. His mother, Abigail Hussey, whom the poet strongly resembled, was of good stock. The Rev. Stephen Bachiler, an Oxford man and a Churchman, who became a Nonconformist and emigrated to Boston in 1632, was one of her forebears and also an ancestor of Daniel Webster. The poet and the statesman showed their kinship by the "dark, deep-set and lustrous eyes" that impressed one who met either of these uncommon men. The former's name of Greenleaf is thought to be derived from the French Feuillevert, and to be of Huguenot origin; and there was Huguenot blood as well in Thomas Whittier, the settler. The poet thus fairly inherited his conscience, religious exaltation and spirit of protest. All the Whittiers were men of stature and bodily strength, John Greenleaf being almost the first exception, a lad of delicate mould, scarcely adapted for the labor required of a Yankee farmer and his household. He bore a fair proportion of it, but throughout his life was frequently brought to a halt by pain and physical debility. In youth he was described as "a handsome young man, tall, slight, and very erect, bashful, but never awkward." His shyness was extreme, though covered by a grave and quiet exterior, which could not hide his love of fun and sense of the ludicrous. In age he retained most of these characteristics, refined by a serene expression of peace after contest. His eyes never lost their glow, and were said by a woman to be those of one "who had kept innocency all his days."

Whittier's early education was restricted to what he could gain from the primitive "district school" of the neighborhood. His call as a poet came when a teacher lent to him the poems of Robert Burns. He was then about fifteen, and his taste for writing, bred thus far upon the quaint Journals of Friends, the Bible and The Pilgrim's Progress, was at once stimulated. There was little art or inspiration in his boyish verse, but in his nineteenth year an older sister thought a specimen of it good enough for submission to the Free Press, a weekly paper which William Lloyd Garrison, the future emancipationist, had started in the town of Newburyport. This initiated Whittier's literary career. The poem was printed with a eulogy, and the editor sought out his young contributor: their alliance began, and continued until the triumph of the anti-slavery cause thirty-seven years later. Garrison overcame the elder Whittier's desire for the full services of his son, and gained permission for the latter to attend the Haverhill academy. To meet expenses the youth worked in various ways, even making slippers by hand in after-hours; but when he came of age his textbook days were ended. Meanwhile he had written creditable student verse, and contributed both prose and rhyme to newspapers, thus gaining friends and obtaining a decided if provincial reputation. He soon essayed journalism, first spending a year and a half in the service of a publisher of two Boston newspapers, theManufacturer, an organ of the Clay protectionists, and the Philanthropist, devoted to humane reform. Whittier edited the former, having a bent for politics, but wrote for the latter also. His father's last illness recalled him to the homestead, where both farm and family became his pious charge. Money had to be earned, and he now secured an editorial post at Hartford, Connecticut, which he sustained until forced by ill-health, early in his twenty-fifth year, to re-seek the Haverhill farm. There he remained from 1832 to 1836, when the property was sold, and the Whittiers removed to Amesbury in order to be near their meeting-house and to enable the poet to be in touch with affairs. The new home became, as it proved, that of his whole later life; a dwelling then bought and in time remodelled was the poet's residence for fifty-six years, and from it, after his death on the 7th of September 1892, his remains were borne to the Amesbury graveyard.

No comments:

Post a Comment